Steve's Last Hurrah: 7 Questions for NNI Co-Founder Dr. Stephen Cornell Before His Last January in Tucson

Dr. Cornell founded Harvard Project on Indigenous Governance and Development (1987) and the Native Nations Institute (2001). He served as Director of the Udall Center from 1998-2016. 2025 will be his last year teaching at January in Tucson.

When we learned that 2025 would be Dr. Stephen Cornell's last year teaching at January in Tucson (JIT), the news was met with mixed emotions.

While we're sad to see one of our longest-standing and most-in-demand course instructors step down from his role at the annual Indigenous governance education event, we're exceedingly grateful that he's participated in the program as long as he has. And, as much as we might want to protest this inevitable departure, we appreciate that the time has come for Dr. Cornell to fully enjoy the retirement that he technically began back in 2018.

Drs. Stephen Cornell and Joe Kalt founded the Harvard Project on Indigenous Governance and Development (then known as the Harvard Project on American Indian Economic Development) in 1987 to begin researching what made some Native American tribes excel in their efforts to strengthen their communities while other Native nations struggled.

In 1998, Dr. Cornell relocated to Tucson, AZ to take over as Director of the Udall Center for Studies in Public Policy and, not long after, he led the development and 2001 launch of the Native Nations Institute at the University of Arizona as a sister institute to the Harvard Project.

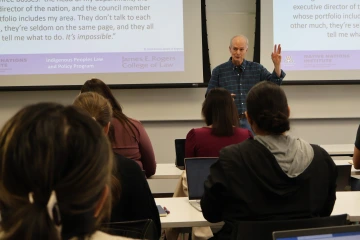

Dr. Cornell was there for the first JIT in 2012 and has been with us for that program teaching multiple courses every year since. His introductory course on Native-nation-building principles continues to be one of the best attended JIT courses year after year and has served as the first step in the Indigenous-governance-related careers of hundreds if not thousands of students.

We sat down with Dr. Cornell to get his take on his experience as a JIT instructor and learn what advice he has for future Native nation builders. Here's what he had to say:

7 Questions with Dr. Stephen Cornell

1) How long have you been teaching?

Stephen Cornell: I taught in the pilot version of JIT that we launched in March of 2012, then in the first full-bore version in 2013, and I believe in all the ones since.

As for teaching more generally, I started teaching sociology in the fall of 1980 after finishing my PhD, so 2025 will mark my forty-fifth year in the biz.

2) What stands out to you as an impactful memory from your time teaching JIT?

SC: From the beginning of the program, I’ve been struck by how much participants in our classes learn from each other.

Most of them are working professionals with substantial ground-level experience serving their nations.

Having the opportunity to mix with professionals like themselves—with people who face similar challenges to those they’re dealing with but in contexts different from their own—this has turned out to be a great learning opportunity.

Part of our job as faculty is to facilitate that sort of connection and exchange.

3) What can students expect to learn in your final JIT courses?

SC: I’m teaching two courses—Rebuilding Native Nations: An Introduction and Comparative Indigenous Governance. I co-teach the latter course with Daryle Rigney, a Ngarrindjeri man and professor at the University of Technology, Sydney.

The first course summarizes the original nation-building research, updates it, considers continuing challenges facing Native nations and lays a foundation for more specialized thinking and learning about Indigenous governance and development.

The second course compares Indigenous governance initiatives and trajectories in four in-some-ways-similar, in-some-ways-different countries: Canada, Australia, Aotearoa New Zealand, and the United States. Its primary purpose is to see if such comparative analysis can have value for Indigenous Peoples trying to assert effective self-governing power.

Does the Aboriginal Australian experience, for example, hold useful lessons for First Nations in Canada, and vice-versa? What could Indigenous nations in the United States learn from experiences elsewhere? The course tries to take advantage of an emerging international network of Indigenous innovation that promotes learning and collaboration across boundaries.

4) Who would benefit from taking your JIT courses?

SC: I think the potential benefit in my courses is similar to that in other courses in JIT. One of the distinguishing features of the program is its emphasis on usable knowledge.

These classes are not really designed for someone who simply has an interest in Indigenous issues, although such people are welcome.

These courses are designed for people—most of them Native—who are working with or for Native nations that, in turn, are struggling to address the catastrophic, long-term impacts of settler colonialism; are trying to reclaim collective self-government as, not only a right, but an effective, daily practice; and are typically engaged in these tasks with limited resources and under sometimes hostile conditions.

Such people are looking for insights they can use, for information that can help them do difficult jobs. We try to respond by translating research into material they can use. We can’t guarantee that everything we do will be useful, but that’s our goal.

5) It’s clear that Nation building concepts are important to Indigenous governance and Native economic development, but is there anything that non-Native scholars can gain by taking JIT courses?

SC: Absolutely.

In the four countries where I’ve done most of my research, Indigenous nations form small, minority populations that are often almost invisible to outsiders.

A lot of what those Indigenous nations are doing happens under the public radar and, in my experience, under the academic radar as well. But many of those nations are engaged in critical, creative, fascinating work that challenges prevailing structures of power and prevailing ideas about Indigenous futures.

I’m a non-Native scholar myself, but learning from and with Indigenous Peoples has been the most challenging and satisfying intellectual adventure of my life. I think other scholars, non-Native like me, can learn a lot from JIT, regardless of the interests driving their own work.

6) How has Native-nation governance changed since you started working in this field?

SC: I’ll answer by paraphrasing something someone with long experience in Indigenous governance and development said to me some years ago.

It went something like this: “When I started in this field, if you went to a conference on Indigenous governance and development, the conversations were all about how to get more government funding. Everyone was looking for good grant writers. You don’t hear that so much anymore. Now the conversations are about how this or that nation took control of an issue and solved it, or expanded their jurisdiction, or reversed the language decline, or brought back ceremony, or revitalized their own law-making. It’s about nations taking control of their futures.”

I agree.

7) What advice do you have for future Nation builders and scholars of Indigenous governance?

SC: Learn from each other.

Many governance problems and challenges are remarkably similar across Indigenous nations, even across international boundaries.

Someone, somewhere, is wrestling with the problem you’re facing—and may be solving it. If you can, connect.